Smoke rose over Dhaka’s streets last week. Islamist mobs attacked newspaper offices and cultural centres. Global headlines screamed of sectarian chaos in Bangladesh. Yet amid the tumult, a different struggle—one with far greater long-term consequences—slipped quietly off the front pages.

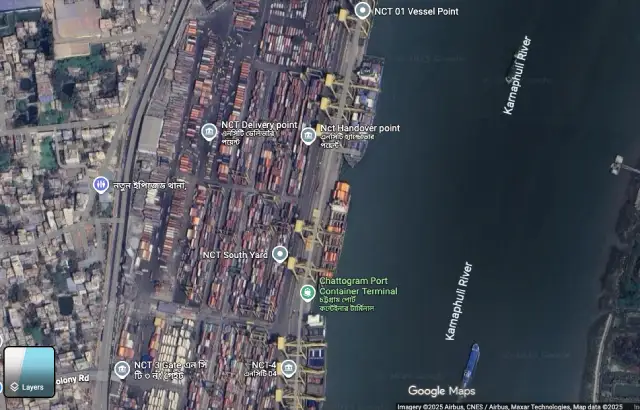

For months, workers, leftists and opposition politicians have battled the interim government’s plan to hand Chittagong Port to foreign corporations. The port handles 92% of Bangladesh’s trade. It employs 50,000 people directly. It generated $420m in revenue last fiscal year. Now, as mob violence consumes public attention, critics fear the movement to save it faces an existential threat.

Critics allege that the mob violence that engulfed Bangladesh on Thursday and Friday, December 18th and 19th, has been a blessing in disguise for the interim government. It’s alleged that the interim government allowed the violence to spread in order to suppress the protests against the handover of the port.

A death, a distraction and diplomatic crisis

The violence began after Sharif Osman Hadi, convener of the far-right Islamist group Inquilab Moncho, died on December 18th. Motorcycle-borne gunmen had shot him six days earlier. Mr Hadi’s supporters identified the attackers as activists from the banned Awami League’s student wing. They allegedly fled to India.

Mr Hadi’s death triggered nationwide unrest. Two social media figures based in the West fanned the flames. Mobs rampaged through the capital. In Mymensingh, they lynched Dipu Das, a Hindu garment worker.

India summoned Bangladesh’s envoy on December 17th to protest the demonstrations that took place outside its mission in Dhaka following the attack on Mr Hadi. The allegations of India sheltering the shooters had fanned the protests. On Sunday, December 21st, Dhaka alleged Hindutva extremists breached its New Delhi mission’s security. New Delhi denied this.

The diplomatic row now dominates headlines. It will likely intensify. Meanwhile, the Muhammad Yunus-led interim government has tightened security nationwide. The Chattogram Metropolitan Police extended its ban on rallies near the port through December. Left-wing activists say this will cripple future protests against the Chittagong port handover.

Port deal that united Bangladesh’s divided opposition

Chittagong Port rarely unites Bangladesh’s fractious political landscape. Yet the privatisation plan has done precisely that.

The Communist Party of Bangladesh (CBP) leads the left bloc’s opposition. Its general secretary, Mohammad Shah Alam, called the handover “anti-national” and accused the government of serving imperialist interests.

The Left Democratic Alliance has organised torch processions. The Anti-Fascist Left Front, and Ganosanhati Andolan have also joined the bandwagon. The left forces, including the CPB, have threatened to “siege” Jamuna, Mr Yunus’s official residence.

The centrist Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) opposes the deal on constitutional grounds. BNP’s acting chairman, Tarique Rahman, declared on May 18th that an interim government lacks the mandate for such strategic decisions. “Such a decision must be taken by a parliament or government elected by the people,” the London-based leader stated.

Even Jamaat-e-Islami, the far-right Islamist party, joined the opposition. Its ameer, Dr Shafiqur Rahman, called the handover “contrary to national interests”. Party leaders raised security concerns about foreign operators near the Bangladesh Navy’s base.

The pro-government National Citizens’ Party struck a nuanced position. It criticised the process but demanded modernisation of port operations as it ranks 356th of 405 globally for efficiency.

What Bangladesh stands to lose at Chittagong

The stakes dwarf any recent economic decision. Chittagong Port handles 98% of Bangladesh’s container traffic. Ships wait four to seven days for turnaround, whereas the global benchmark is under 24 hours. Containers sit for 11 days on average, whereas elsewhere, the standard is three days.

The interim government argues foreign operators will fix this. APM Terminals, a Maersk subsidiary, signed a 33-year deal worth $550m for Laldia Container Terminal in November 2024. Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Gateway took Patenga Container Terminal for 22 years. Switzerland’s Medlog secured Pangaon Inland Terminal.

The most contentious prize remains the New Mooring Container Terminal (NCT). It handles 44% of all container traffic. It earned $127m in revenue last fiscal year. Bangladesh built it domestically for $226m in 2007. It already turns a profit.

The UAE’s DP World wants NCT for 25-30 years. But a December 4th High Court hearing produced a split verdict. Justice Fatema Najib ruled the contract process illegal. Justice Fatema Anwar rejected the petition on standing grounds. A third judge will hear the case after January.

Port workers fear the worst. Over 1,000 NCT employees face potential job losses under DP World. The Sramik Karmachari Oikya Parishad, representing 90% of unionised workers, issued a 13-point demand charter. They want all privatisation halted.

However, the interim government, headed by Mr Yunus, known to be a man whom the West trusts, remains mute.

West-based Bangladeshi social media provocateurs remain mum on the issue, although they decry losing sovereignty every now and then.

Why the timing raises suspicions

Critics see a pattern in recent events. The port protests peaked in early December. Earlier, the port workers staged a mass hunger strike on November 1st. On November 20th, intellectuals raised objections over the deal. The workers blockaded three port entry points on November 26th. A red-flag march proceeded on December 10th.

Then came Mr Hadi’s shooting on December 12th. Then his death, a week later. Then the mob violence gripped Bangladesh. Then the security crackdowns.

Left-wing activists do not call this a coincidence. They note that Bangladesh has witnessed Islamist mob violence since the 1980s, when petrodollars funded Salafist politics during the Cold War. What differs now, they argue, is the timing’s convenience for those pushing the port deal forward.

The interim government remained passive during the post-death unrest. It tightened security only after the violence subsided. Those restrictions now hamper the very movements opposing its economic policies.

Professor Anu Muhammad of the Democratic Rights Committee articulated the constitutional objection clearly. “The interim government has no jurisdiction to enter into such long-term agreements,” he stated. “The people did not bring this interim government to power through the mass uprising to make such decisions.”

Regional precedents offer warnings

Handing over ports to foreign operators seldom brings better results. Bangladesh’s neighbours provide cautionary tales. Pakistan handed Gwadar Port to China Overseas Port Holding Company in 2013 on a 43-year lease. By 2022-23, Gwadar handled just 1% of Pakistan’s seaborne trade. China retains 91% of marine revenue. Local communities, especially Balochs, protest displacement and broken promises. The Gwadar Port area remains a volatile region for this reason.

Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port passed to China Merchants Port Holdings in 2017 on a 99-year lease. The debt-for-equity swap became a global symbol of sovereignty lost through infrastructure financing.

Even DP World, now negotiating for NCT, faced rejection elsewhere. In 2006, the US Congress blocked its acquisition of six American port terminals on national security grounds. Bangladeshi opponents ask why similar logic should not apply to their country.

Moreover, Chittagong is a strategic location for Bangladesh. It not only houses the port, Bangladesh’s lifeline, but it’s also close to India’s restive northeast and war-torn Myanmar. Handing over a crucial strategic asset located in the region to foreign corporations also raises national security concerns.

What comes next for Bangladesh and Chittagong port

The legal battle continues. The High Court’s split verdict means uncertainty until a third judge rules. The interim government shows no sign of retreat. Mr Yunus has made port reform a signature priority.

Mr Yunus’s critics call his hasty move a part of a well-planned scheme that aims at promoting the West’s interests in the country before the national elections.

Meanwhile, in the post-Hadi phase, the street movements face unprecedented obstacles. Security restrictions will help curb dissent. Diplomatic tensions with India will consume political bandwidth. The mob violence narrative will continue to sink economic concerns in international coverage.

The irony is stark. A government born from a popular uprising now ignores popular opposition on economic sovereignty. A port that belongs to Bangladesh’s people may pass to foreign hands while those people focus on sectarian fires.

The world watches Bangladesh’s religious violence. It pays less attention to a quieter struggle over the nation’s commercial lifeline.

That inattention may prove the interim government’s greatest asset in pushing the Chittagong port deal through.

For workers, leftists and opposition politicians, the battle continues. They must now wage it under far harder conditions.

Join our channels on Telegram and WhatsApp to receive geopolitical updates, videos and more.