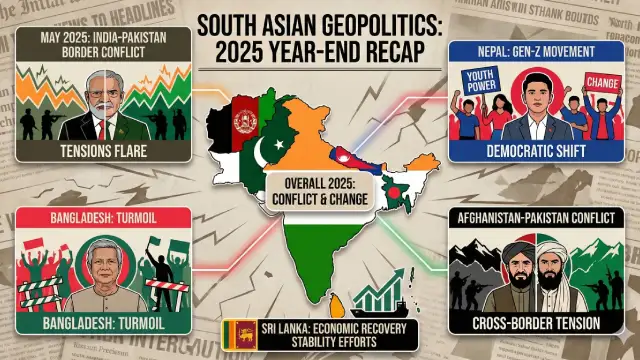

The year began with hope for stability. It ended with two nuclear powers exchanging missile fire, a teenage movement toppling a government, and a devastating cyclone threatening to reverse years of economic recovery. South Asian geopolitics in 2025 will be remembered as a turning point. The old order—built around Indian dominance and US partnership—cracked under the weight of popular uprisings, great-power competition and long-simmering resentments. What emerged was messier, more contested and more dangerous.

On April 22nd, five armed militants attacked tourists at Baisaran Valley near Pahalgam in Kashmir. They killed 26 civilians. Twenty-five were Hindu pilgrims; one was a Nepalese Christian. The Resistance Front, believed to be linked to Lashkar-e-Taiba, initially claimed responsibility. Within hours, India suspended the Indus Waters Treaty. The 65-year-old agreement had survived three wars. It did not survive 2025.

New Delhi closed the Attari-Wagah border crossing. It cancelled all Pakistani visas and expelled diplomats. Islamabad responded by suspending the Simla Agreement of 1972. It closed its airspace to Indian aircraft and halted bilateral trade. The subcontinent’s nuclear-armed rivals were hurtling toward conflict.

‘Operation Sindoor’: Subcontinental war returns

On the intervening night of May 6th-7th, India launched “Operation Sindoor”. Missiles and warplanes struck nine sites across Pakistan. Targets included Lashkar-e-Taiba’s headquarters at Muridke and Jaish-e-Mohammed facilities in Bahawalpur. India claimed its strikes killed more than 100 militants. Pakistan reported 31 civilian casualties.

Pakistan’s retaliation came swiftly. Heavy artillery shelling struck the Poonch district in Jammu. Seventeen civilians died, including 12-year-old twins. It was the worst shelling since 1971. The conflict introduced drone warfare between nuclear powers.

Pakistan claimed it shot down 77 Israeli-made Harop drones. Islamabad also claimed it had shot down five Indian fighter jets, including the much-hyped Rafale jets.

India rejected the claims initially, but didn’t release any official data on losses. Later, India’s defence attache in Indonesia, Indian Navy Captain Shiv Kumar, acknowledged that India had lost some planes.

“I may not agree with him that India lost so many aircraft. But I do agree that we did lose some aircraft and that happened only because of the constraint given by the political leadership to not attack the military establishments and their air defences,” Captain Kumar said. A Navy captain is equivalent to an Army colonel.

Captain Kumar’s statement triggered a furore in India’s political landscape. The Opposition, which joined Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s endeavour to highlight the importance of India’s Operation Sindoor across different countries, questioned the government’s reluctance to hit Pakistani military installations.

India’s Air Chief Marshal AP Singh, in October, claimed India had shot down five Pakistani jets, including F-16s and JF-17s. This was the first time India mentioned the makes of the planes it had claimed to have shot down.

On May 10th, Pakistan launched Operation Bunyan-um-Marsoos. Its forces targeted Indian airbases and reportedly struck an S-400 missile system at Adampur. India denied the claim. An alleged US-mediated ceasefire followed the same day.

Approximately 70 people had died on both sides in the conflict. Several Indian civilians were killed by Pakistani shelling in Jammu. The guns fell silent, but the loss of scores of lives shaped South Asian geopolitics in 2025.

The aftermath left critical bilateral mechanisms suspended. The Indus Waters Treaty remains frozen. Trade has halted. The Kartarpur Corridor stands closed. Diplomatic staff have been reduced to skeleton crews.

Later, Pakistan signed a mutual defence pact with Saudi Arabia. It’s claimed that both countries will come to each other’s rescue if one of them faces an attack. The deal followed the Israeli attack on Qatar. The Pakistan-Saudi Arabia pact made New Delhi anxious.

In December, Pakistan proposed a new South Asian bloc with Bangladesh and China, explicitly excluding India. The region’s architecture was being redrawn.

Bangladesh turns eastward as India-Dhaka relations collapse

The ouster of Sheikh Hasina‘s government in August 2024 set the stage for a dramatic rupture. Throughout 2025, relations between Dhaka and New Delhi deteriorated to their lowest point in decades. The International Crisis Group warned the two neighbours were “lurching toward crisis.”

Border violence dominated early 2025. India’s Border Security Force (BSF) killed multiple Bangladeshi nationals between January and March. Data showed 34 Bangladeshis killed by the BSF during the interim government’s first 11 months. Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) Director General Maj Gen Ashrafuzzaman warned of a “stronger response” if killings continued.

From May 7th onwards, India’s BSF pushed over 1,600 individuals into Bangladesh. They included Rohingya refugees and Indian Muslims allegedly tortured and expelled from Gujarat and other states. Bangladesh sent formal protest letters. It has called the push-ins violations of the 1975 joint guidelines.

India imposed escalating trade restrictions. In April, it suspended the transhipment facility for Bangladeshi garment exports. Port restrictions forced Bangladesh to reroute shipments through Colombo and Dubai. Costs soared. Bangladesh responded by blocking Indian yarn imports.

Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus chose China for his first bilateral visit. He travelled to Beijing in late March. China committed $2.1bn in investments. It welcomed participation in the $1bn Teesta River project. Foreign Adviser Touhid Hossain stated publicly that Bangladesh’s relationship with India “needs to be rebalanced.” The pivot was unmistakable.

Ms Hasina’s extradition issue became a diplomatic flashpoint. On Nov 17th, Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal sentenced the former prime minister to death for crimes against humanity. Bangladesh sent two extradition requests. India said they were “being examined.” Compliance appears unlikely. In December, Bangladesh summoned India’s High Commissioner. The charge, Ms Hasina was making “incendiary statements” from Indian soil.

December brought further escalation. A prominent young Islamist leader was assassinated in Bangladesh. His death sparked mob violence across the country.

An Islamist mob in Mymensingh lynched Dipu Chandra Das, a Hindu factory worker. The incident triggered protests outside Bangladesh missions in India. Both countries summoned each other’s envoys. Bangladesh suspended consular services in Delhi and Agartala. South Asian geopolitics offered few signs of reconciliation in 2025.

Russia recognises Taliban as great powers court Kabul

On July 3rd, Russia became the first country to formally recognise the Taliban as Afghanistan’s legitimate government. Moscow had removed the Taliban from its terrorist list in April. It elevated diplomatic representation to an ambassadorial level. The recognition aimed to restore Russian influence in a region where Moscow had faced setbacks.

The Taliban’s most serious external crisis came in October. Conflict with Pakistan reached unprecedented intensity. A TTP ambush killed 11 Pakistani soldiers on October 8th. Pakistan launched airstrikes on Kabul, Khost, Jalalabad and Paktika the following day. It targeted TTP leader Noor Wali Mehsud.

Afghan Taliban forces retaliated fiercely. They attacked 27 Pakistani military posts. Reports suggested 58 Pakistani soldiers died. UNAMA documented 37 civilians killed and 425 injured before a Qatar-mediated ceasefire on October 19th.

In a significant pivot, Taliban Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi made a historic visit to India. He arrived on October 9th and stayed until October 12th. It was the highest-level Taliban engagement since 2021. India upgraded its Kabul mission to full embassy status. It announced six development projects. It launched an air freight corridor. Afghan-India bilateral trade had reached $598.8m in Afghan exports to India.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Kabul in August. He invited Afghanistan to formally join the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). He announced “practical mining activities” would begin. The Chinese have focused on lithium, copper and the massive Mes Aynak copper mine.

The International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants on July 8th. It charged Supreme Leader Haibatullah Akhundzada and Chief Justice Abdul Hakim Haqqani with crimes against humanity. The charges included persecution on gender and political grounds. The Taliban dismissed the warrants as “baseless rhetoric.”

The humanitarian crisis remained severe. Nearly 23m people require assistance. Some 2.6m Afghans were returned or deported from Iran and Pakistan. A 6.3-magnitude earthquake on August 31st killed over 2,150 people in eastern Afghanistan. The US halted all remaining humanitarian assistance in April. That funding had previously constituted 47% of the total.

Nepal’s Gen Z uprising and the fall of Oli

September 8th transformed Nepal’s political landscape. Youth-led anti-corruption protests escalated into violence that toppled Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli‘s government. The movement began as opposition to a government-imposed social media ban. It expanded into demands for good governance and transparency.

On September 8th, police fired rubber bullets and tear gas. At least 19 people died. Violence escalated dramatically the next day. Parts of the Federal Parliament, the Supreme Court and ministers’ homes were set ablaze. Mr Oli’s private residence came under attack. Over 70 people died during the two days of unrest. Property damage reached an estimated Rs 84.45bn. Oli resigned.

Gen Z representatives negotiated with Army Chief General Ashok Raj Sigdel. They proposed former Chief Justice Sushila Karki as interim prime minister. On September 12th, Karki was sworn in as Nepal’s first woman head of government. The House of Representatives was dissolved. Elections are scheduled for March 5th, 2026.

A ten-point agreement signed on December 10th recognised the uprising as “a political-social people’s movement.” It granted amnesty to participants. It declared 45 of 76 deaths as martyrs. It established term limits for party leaders. South Asian geopolitics had witnessed another popular uprising reshape a nation in 2025.

Nepal found itself caught between India and China on the Lipulekh Pass controversy. India and China agreed on August 18th to reopen the trade route. Nepal claims the territory as its own. Kathmandu sent diplomatic notes to both capitals protesting the agreement. India’s External Affairs Ministry called Nepal’s claims “untenable.”

Energy cooperation remained a bright spot. Major agreements in 2025 included joint ventures for two 400kV transmission lines connecting the countries. Nepal targets 10,000 MW in electricity exports to India by 2034. Its electricity exports already reached 1,010.9 MW.

Sri Lanka’s recovery threatened by Cyclone Ditwah

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake‘s left-wing National People’s Power (NPP) government made substantial progress on economic recovery throughout 2025. The IMF completed four reviews of Sri Lanka’s Extended Fund Facility (EFF). It disbursed approximately $1.74bn till June 2025 under EFF. GDP grew 5% in 2024 and 4.8% year-on-year in the first half of 2025. External creditors forgave $3bn and restructured $25bn over 20 years.

Sri Lanka navigated great-power competition skilfully. Mr Modi visited in early April. The visit produced seven memoranda of understanding covering defence cooperation and a trilateral Trincomalee Energy Hub with UAE involvement. India received the “Sri Lanka Mitra Vibhushana”—the highest civilian honour for foreign leaders.

Mr Dissanayake visited China in January. He secured 15 MoUs and the $3.7bn Sinopec oil refinery agreement for Hambantota. It was Sri Lanka’s largest single foreign direct investment commitment ever. China pledged potential investments totalling $10bn. The April launch of the Colombo West International Terminal demonstrated Sri Lanka’s ability to attract investment from both Asian giants.

Then Cyclone Ditwah struck on November 28th. Mr Dissanayake described it as the “largest and most challenging natural disaster” in Sri Lanka’s history. The cyclone killed 643 people. Another 183 remain missing. Nearly two million people—10% of the population—were affected. Over 107,000 homes were destroyed. Damage estimates ranged from $4.1bn to $7bn.

The agricultural sector suffered devastating losses. The cyclone destroyed 108,000 hectares of rice paddies. Tea output is projected to decline by 35%. India immediately launched Operation Sagar Bandhu. It deployed the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant and INS Udaygiri to deliver emergency relief.

The IMF approved a $206m Rapid Financing Instrument on December 19th for disaster response. Over 121 economists, including Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, called for IMF debt payment suspension. They noted Sri Lanka must dedicate 25% of revenue to debt servicing. South Asian geopolitics had delivered another cruel blow in 2025.

Myanmar’s civil war under Chinese management

Myanmar’s civil war evolved in 2025 under significant Chinese influence. Beijing brokered arrangements that reversed some resistance gains. The junta staged widely condemned elections. By late 2025, the military reportedly controlled only about 21% of the country.

In January, China brokered a ceasefire between the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and the junta. The deal reportedly required withdrawal from the strategic town of Lashio. By April, under Chinese supervision, Lashio was handed back to the junta without fighting. It was a major setback for resistance forces. Chinese Special Envoy Deng Xijun pressured the Kachin Independence Army and Arakan Army to halt offensives near Belt and Road Initiative infrastructure.

The Arakan Army emerged as the most successful ethnic armed group. It captured 14 of 17 Rakhine townships plus Paletwa in Chin State. The AA now controls the entire western border with India and Bangladesh. It continues to besiege the state capital, Sittwe.

A devastating 7.7-magnitude earthquake on March 28th killed approximately 3,739 people. It affected over 500,000 across Sagaing, Mandalay and Shan State. The junta continued airstrikes—27 reported in the week following the quake.

The junta proceeded with elections on December 28th in 102 townships. It excluded 56 due to insecurity. Western diplomats, the UN and opposition forces condemned the vote. ASEAN refused to send observers. China’s legitimisation efforts suffered a blow.

Refugee implications intensified for the region. Over 1 million Rohingya remain in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar camps. Some 70,000 arrived in 2024. Another 100,000 or more arrived in early 2025. In May, two boats carrying 514 Rohingya sank. They possibly killed 427 people—the deadliest sea tragedy for the Rohingya in 2025.

China expands its footprint through BRI investments

China significantly expanded its BRI presence across South Asia in 2025. Major developments occurred in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bangladesh.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) Phase 2 received substantial impetus during Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s September visit to Beijing. Pakistan and China signed 21 MoUs worth $8.5bn. The 14th Joint Cooperation Committee meeting launched CPEC 2.0’s five new corridors—Growth, Livelihood, Innovation, Green and Openness. Key announcements included Haier’s $400m home appliance industrial park. Total CPEC investment since inception has reached $25.93bn.

Sri Lanka’s January presidential visit to Beijing secured the $3.7bn Sinopec refinery deal for Hambantota. Notably, no new Chinese loans have been extended since 2021. Beijing has shifted toward direct investment.

Nepal signed the BRI Cooperation Framework in December 2024. It covers 10 projects, including the Jilong-Kerung-Kathmandu cross-border railway. Progress remained slow. Most projects stayed at the pre-feasibility stage. Nepal insisted on grants rather than loans. Officials stated the country “cannot afford to take loans with its own compulsions and grim economic situation.”

Bangladesh celebrated the 50th anniversary of diplomatic ties with China. The BRI has created nearly 600,000 jobs in Bangladesh over nine years. China has been Bangladesh’s largest trading partner for 15 consecutive years. Mr Yunus stated Chinese investments will be a “game-changer.”

Washington recalibrates under Trump’s second term

Donald Trump’s administration fundamentally recalibrated US South Asia policy in 2025. It notably elevated Pakistan’s strategic importance following the May conflict.

US-India relations maintained their strategic trajectory but faced tensions. Mr Modi met Mr Trump in February. They launched the “US-India COMPACT” targeting $500bn bilateral trade by 2030. Defence trade has grown from near zero in 2008 to over $20bn.

However, Mr Trump imposed higher tariffs on India than on China. He criticised India’s purchases of Russian oil. The extra 25% punitive tariffs on India raised questions about Mr Modi’s diplomatic skills.

Pakistan experienced dramatic rehabilitation. Following the May conflict, Washington perceived Pakistan’s crisis management as more flexible than India’s. In December, the US approved a $686m package for upgrading Pakistan’s F-16 fighters. Mr Trump hosted Pakistani Army Chief Field Marshal Asim Munir for a luncheon unaccompanied by civilian officials. It was unprecedented for a US president. The November 2025 National Security Strategy termed Pakistan a “key ally.”

QUAD activities continued, but faced questions about relevance. The July Foreign Ministers’ Meeting announced the QUAD Critical Minerals Initiative. It condemned the Pahalgam attack. Analysts described QUAD as “adrift and increasingly marginal to US strategy” under Mr Trump. It received only a single mention in the November National Security Strategy. South Asian geopolitics saw Washington’s priorities shift in 2025.

US engagement with Bangladesh focused on the upcoming February 2026 elections. Ambassador nominee Brent Christensen described them as “the most consequential election in decades.” Bangladesh faces a 20% tariff under Mr Trump’s trade measures. This gives Dhaka a competitive leverage vis-à-vis New Delhi.

Regional cooperation paralysed as SAARC turns 40

SAARC marked its 40th anniversary on December 8th, 2025. The organisation remains moribund. No summit has been held since Kathmandu 2014. India-Pakistan rivalry prevents meaningful engagement. Dawn’s editorial described SAARC as “an unfulfilled dream, marked more by lost potential than any significant achievement.”

BIMSTEC provided an alternative forum. The 6th Summit in Bangkok on April 4th adopted the landmark Bangkok Vision 2030. It was the first strategic blueprint for the organisation. Major outcomes included a Maritime Transport Agreement to reduce shipping costs. Mr Modi announced a 21-point action plan. It included linking India’s UPI with regional payment systems.

The summit notably featured the Yunus-Modi bilateral meeting. It was the only substantive engagement between the two leaders in 2025. Bangladesh assumed the chairmanship from Thailand. BIMSTEC included Myanmar’s Min Aung Hlaing despite the junta’s pariah status in other forums.

Region reorders itself

The events of 2025 represent not merely a turbulent year but a structural transformation. The India-Pakistan military exchange demonstrated that nuclear deterrence no longer prevents limited conventional conflict. The suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty removed a pillar of subcontinental stability.

Bangladesh’s decisive turn toward Beijing under Mr Yunus’s interim government suggests the end of Dhaka’s strategic dependence on New Delhi. India’s counterproductive responses accelerated the shift. The Taliban’s normalisation continues apace. Russian recognition, Indian engagement and Chinese investment create facts on the ground. The international community will struggle to reverse them.

Popular uprisings in Nepal followed Sri Lanka in 2022 and Bangladesh in 2024. They suggest a regional pattern. Youth-led movements reject corrupt establishment politics across South Asia.

The US policy shift toward elevating Pakistan represents a departure from the “India First” approach of recent decades. Washington’s South Asia calculus appears subordinated to broader great-power competition with China. The region enters 2026 facing Bangladesh’s crucial election in February. Nepal votes in March. India and Pakistan remain frozen at their lowest point in half a century.

South Asian geopolitics delivered upheaval on multiple fronts in 2025. Popular movements, military exchanges, natural disasters and great-power competition reshaped the region’s contours. China emerged as the principal external beneficiary of South Asia’s disorder. The old order has cracked. What replaces it remains dangerously unclear.

Join our channels on Telegram and WhatsApp to receive geopolitical updates, videos and more.